The code & sample apps can be found on Github

Today I’m going to write about a Proof of Concept I’ve been working on those last weeks: I wanted to use scalaz-stream as a driver of Spark distributed data processing. This is simply an idea and I don’t even know whether it is viable or stupid. But the idea is interesting!

Introduction

2 of my preferred topics those last months are :

- Realtime streaming

- Realtime clustered data processing (in-memory & fault-tolerant)

2 tools have kept running through my head those last months:

Scalaz-Stream for realtime/continuous streaming using pure functional concepts: I find it very interesting conceptually speaking & very powerful, specially the deterministic & non-deterministic demuxtiplexers provided out-of-the-box (Tee & Wye).

Spark for fast/fault-tolerant in-memory, resilient & clustered data processing.

I won’t speak much about Scalaz-Stream because I wrote a few articles about it.

Let’s focus on Spark.

Spark provides tooling for cluster processing of huge datasets in the same batch mode way as Hadoop, the very well known map/reduce infrastructure. But at the difference of Hadoop which is exclusively relying on HDFS cluster file systems when distributing data through the cluster, Spark tries to cache data in memory as much as possible so that latency of access is reduced as much as possible. Hadoop can scale a lot but is known to be slow in the context of a single node.

Spark is aimed at scaling as much as Hadoop but running faster on each node using in-memory caching. Fault-tolerance & data resilience is managed by Spark too using persistence & redundancy based on any nice storage like HDFS or files or whatever you can plug on Spark. So Spark is meant to be a super fast in-memory, fault-tolerant batch processing engine.

RDD Resilient Distributed Dataset

The basic concept of Spark is Resilient Distributed Dataset aka RDD which is a read-only, immutable data structure representing a collection of objects or dataset that can be distributed across a set of nodes in a cluster to perform map/reduce style algorithms.

The dataset represented by this RDD is partitioned i.e. cut into slices called partitions that can be distributed across the cluster of nodes.

Resilient means these data can be rebuilt in case of fault on a node or data loss. To perform this, the dataset is replicated/persisted across nodes in memory or in distributed file system such as HDFS.

So the idea of RDD is to provide a seamless structure to manage clustered datasets with very simple API in “monadic”-style :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

Depending on your SparkContext configuration, Spark takes in charge of distributing behind the curtain your data to the cluster nodes to perform the required processing in a fully distributed way.

One thing to keep in mind is that Spark distributes data to remote nodes but it also distributes the code/closures remotely. So it means your code has to be serializable which is not the case of scalaz-stream in its current implementation.

Just a word on Spark code

As usual, before using Spark in any big project, I’ve been diving in its code to know whether I can trust this project. I must say I know Spark’s code better than its API ;)

I find Spark Scala implementation quite clean with explicit choices of design made clearly in the purpose of performance. The need to provide a compatible Java/Python API and to distribute code across clustered nodes involves a few restrictions in terms of implementation choices. Anyway, I won’t criticize much because I wouldn’t have written it better and those people clearly know what they do!

Spark Streaming

So Spark is very good to perform fast clustered batch data processing. Yet, what if your dataset is built progressively, continuously, in realtime?

On top of the core module, Spark provides an extension called Spark Streaming aiming at manipulating live streams of data using the power of Spark.

Spark Streaming can ingest different continuous data feeds like Kafka, Flume, Twitter, ZeroMQ or TCP socket and perform high-level operations on it such as map/reduce/groupby/window/…

DStream

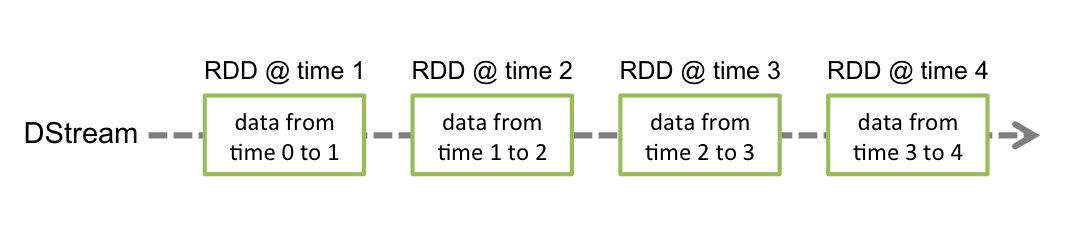

The core data structure behind Spark Streams is DStream for Discretized Stream (and not distributed).

Discretized means it gets a continuous stream of data and makes it discrete by slicing it across time and wrapping those sliced data into the famous RDD described above.

A DStream is just a temporal data partitioner that can distribute data slices across the cluster of nodes to perform some data processing using Spark capabilities.

Here is the illustration in official Spark Stream documentation:

DStream also tries to leverage Spark automated persistence/caching/fault-tolerance to the domain of live streaming.

DStream is cool but it’s completely based on temporal aspects. Imagine you want to slice the stream depending on other criteria, with DStream, it would be quite hard because the whole API is based on time. Moreover, using DStream, you can discretize a dataflow but you can’t go in the other way and make it continuous again (in my knowledge). This is something that would be cool, isn’t it?

If you want to know more about DStream discretization mechanism, have a look at the official doc.

As usual, I’m trying to investigate the edge-cases of concepts I like. In general, this is where I can test the core design of the project and determine whether it’s worth investigating in my every-day life.

Driving Spark Streams with Scalaz-Stream

I’ve been thinking about scalaz-stream concepts quite a lot and scalaz-stream is very good at manipulating continuous streams of data. Moreover, it can very easily partition a continuous stream regrouping data into chunks based on any criteria you can imagine.

Scalaz-stream represents a data processing algorithm as a static state machine that you can run when you want. This is the same idea behind map/reduce Spark API: you build your chain of map/filter/window and finally reduce it. Reducing a spark data processing is like running a scalaz-stream machine.

So my idea was the following:

- build a continuous stream of data based on scalaz-stream

Process[F, O]- discretize the stream

Process[F, O] => Process[F, RDD[O]]- implement count/reduce/reduceBy/groupBy for

Process[F, RDD[O]]- provide a

continuizemethod to doProcess[F, RDD[O]] => Process[F, O]

So I’ve been hacking between Scalaz-stream Process[F, O] & Spark RDD[O] and here is the resulting API that I’ve called ZPark-ZStream (ZzzzzzPark-Zzzzztream).

Let’s play a bit with my little alpha API.

Discretization by simple slicing

Let’s start with a very simple example.

Take a simple finite process containing integers:

1

| |

Now I want to slice this stream of integer by slices of 4 elements.

First we have to create the classic Spark Streaming context and make it implicit (needed by my API).

Please remark that I could plug existing StreamingContext on my code without any problem.

1 2 | |

Then let’s parallelize the previous process :

1 2 3 | |

Ok folks, now, we have a discretized stream of Long that can be distributed across a Spark cluster.

DStream provides count API which count elements on each RDD in the stream.

Let’s do the same with my API:

1

| |

What happens here? The `count operation on each RDD in the stream is distributed across the cluster in a map/reduce-style and results are gathered.

Ok that’s cool but you still have a discretized stream Process[Task, RDD[Int]] and that’s not practical to use to see what’s inside it. So now we are going to re-continuize it and make it a Process[Task, Int] again.

1

| |

Easy isn’t it?

All together :

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Let’ print the result in the console

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

Oh yes that works: in each slice of 4 elements, we actually have 4 elements! Reassuring ;)

Let’s do the same with countByValue:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

You can see that 4 comes before 3. This is due to the fact the 2nd slice of 4 elements (3,3,4,4) is converted into a RDD which is then partitioned and distributed across the cluster to perform the map/reduce count operation. So the order of return might be different at the end.

An example of map/reduce ?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Please note that:

1

| |

Discretization by time slicing

Now we could try to slice according to time in the same idea as DStream

First of all, let’s define a continuous stream of positive integers:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Now, I want integers to be emitted at a given tick for example:

1 2 | |

Then, let’s discretize the continuous stream with ZPark-Ztream API:

1 2 | |

The stream is sliced in slice of 500ms and all elements emitted during these 500ms are gathered in a Spark RDD.

On this stream of RDD, we can applycountRDD` as before and finally re-continuize it. All together we obtain:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | |

Approximatively we have 50 elements per slice which looks like what we expected.

Please note that there is a short period of warmup where values are less homogenous.

Discretization by time slicing keeping track of time

DStream keeps track of all created RDD slices of data (following Spark philosophy to cache as much as possible) and allows to do operation of windowing to redistribute RDD.

With ZPark API, you can write the same as following:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

We can see here that final interval haven’t 100 elements as we could expect. This is still a mystery to me and I must investigate a bit more to know where this differences comes from. I have a few ideas but need to validate.

Anyway, globally we get 500 elements meaning we haven’t lost anything.

Mixing scalaz-stream IO & Spark streaming

Playing with naturals is funny but let’s work with a real source of data like a file.

It could be anything pluggable on scalaz-stream like kafka/flume/whatever as DStream provides…

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | |

Infusing tee with RDD Processes

Is it possible to combine RDD Processes using scalaz-stream ?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | |

Please note that I drive Spark RDD stream with Scalaz-Stream always remains on the driver node and is never sent to a remote node as map/reduce closures are in Spark. So Scalaz-stream is used a stream driver in this case. Moreover, Scalaz Process isn’t serializable in its current implementation so it wouldn’t be possible as is.

What about persistence & fault tolerance?

After discretizing a process, you can persist each RDD :

1

| |

Ok but DStream does much more trying to keep in-memory every RDD that is generated and potentially persist it across the cluster. This makes things stateful & mutable which is not the approach of pure functional API like scalaz-stream. So, I need to think a bit more about this persistence topic which is huge.

Anyway I believe I’m currently investigating another way of manipulating distributed streams than DStream.

Conclusion

Spark is quite amazing and easy to use with respect to the complexity of the subject.

I was also surprised to be able to use it with scalaz-stream so easily.

I hope you liked the idea and I encourage you to think about it and if you find it cool, please tell it! And if you find it stupid, please tell it too: this is still a pure experiment ;)

Have a look at the code on Github.

Have distributed & resilient yet continuous fun!