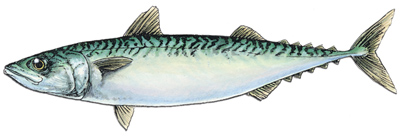

Maquereau [Scomber Scombrus]

[/makʀo/] in french phonetics

Since I discovered Scala Macros with Scala 2.10, I’ve been really impressed by their power. But great power means great responsibility as you know. Nevertheless, I don’t care about responsability as I’m just experimenting. As if mad scientists couldn’t experiment freely!

Besides being a very tasty pelagic fish from scombroid family, Maquereau is my new sandbox project to experiment eccentric ideas with Scala Macros.

Here is my first experiment which aims at studying the concepts of pataphysics applied to Scala Macros.

Pataphysics applied to Macros

Programming is math

I’ve heard people saying that programming is not math.

This is really wrong, programming is math.

And let’s be serious, how would you seek attention in urbane cocktails without those cute little words such as functors, monoids, contravariance, monads?

She/He> What do you do?

You> I’m coding a list fold.

She/He> Ah ok, bye.

You> Hey wait…

She/He> What do you do?

You> I’m deconstructing my list with a catamorphism based on a F-algebra as underlying functor.

She/He> Whahhh this is so exciting! Actually you’re really sexy!!!

You> Yes I known insignificant creature!

Programming is also a bit of Physics

Code is static meanwhile your program is launched in a runtime environment which is dynamic and you must take these dynamic aspects into account in your code too (memory, synchronization, blocking calls, resource consumption…). For the purpose of the demo, let’s accept programming also implies some concepts of physics when dealing with dynamic aspects of a program.

Compiling is Programming Metaphysics

Between code and runtime, there is a weird realm, the compiler runtime which is in charge of converting static code to dynamic program:

- The compiler knows things you can’t imagine.

- The compiler is aware of the fundamental nature of math & physics of programming.

- The compiler is beyond these rules of math & physics, it’s metaphysics.

Macro is Pataphysics

Now we have Scala Macros which are able:

- to intercept the compiling process for a given piece of code

- to analyze the compiler AST code and do some computation on it

- to generate another AST and inject it back into the compile-chain

When you write a Macro in your own code, you write code which runs in the compiler runtime. Moreover a macro can go even further by asking for compilation from within the compiler: c.universe.reify{ some code }… Isn’t it great to imagine those recursive compilers?

So Scala macro knows the fundamental rules of the compiler. Given compiler is metaphysics, Scala macro lies beyond metaphysics and the science studying this topic is called pataphysics.

This science provides very interesting concepts and this article is about applying them to the domain of Scala Macros.

I’ll let you discover pataphysics by yourself on wikipedia

Let’s explore the realm of pataphysics applied to Scala macro development by implementing the great concept of patamorphism, well-known among pataphysicians.

Defining Patamorphism

In 1976, the great pataphysician, Ernst Von Schmurtz defined patamorphism as following:

A patamorphism is a patatoid in the category of endopatafunctors…

Explaining the theory would be too long with lots of weird formulas. Let’s just skip that and go directly to the conclusions.

First of all, we can consider the realm of pataphysics is the context of Scala Macros.

Now, let’s take point by point and see if Scala Macro can implement a patamorphism.

A patamorphism should be callable from outside the realm of pataphysics

A Scala macro is called from your code which is out of the realm of Scala macro.

A patamorphism can’t have effect outside the realm of pataphysics after execution

This means we must implement a Scala Macro that :

- has effect only at compile-time

- has NO effect at run-time

From outside the compiler, a patamorphism is an identity morphism that could be translated in Scala as:

1

| |

A patamorphism can change the nature of things while being computed

Even if it has no effect once applied, meanwhile it is computed, it can :

- have side-effects on anything

- be blocking

- be mutable

Concerning these points, nothing prevents a Scala Macro from respecting those points.

A patamorphism is a patatoid

You may know it but patatoid principles require that the morphism should be customisable by a custom abstract seed. In Scala samples, patatoid are generally described as following:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

So a patamorphism could be implemented as :

1

| |

A custom patamorphism implemented as a Scala Macro would be written as :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

But in current Scala Macro API, this is not possible for a Scala Macro to override an abstract function so we can’t write it like that and we need to trick a bit. Here is how we can do simply :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | |

Conclusion

We have shown that we could implement a patamorphism using a Scala Macro.

But the most important is the implementation of the macro which shall:

- have effect only at compile-time (with potential side-effect, sync, blocking)

- have NO effect at runtime

Please note that pataphysics is the science of exceptions so all previous rules are true as long as there are no exception to them.

Let’s implement a 1st sample of patamorphism called VerySeriousCompiler.

Sample #1: VerySeriousCompiler

What is it?

VerySeriousCompiler is a pure patamorphism which allows to change compiler behavior by :

- Choosing how long you want the compilation to last

- Displaying great messages at a given speed while compiling

- Returning the exact same code tree given in input

VerySeriousCompiler is an identity morphism returning your exact code without leaving any trace in AST after macro execution.

VerySeriousCompiler is implemented exactly using previous patamorphic pattern and the compiling phase can be configured using custom Seed:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

When to use it?

VerySeriousCompiler is a useful tool when you want to have a coffee or discuss quietly at work with colleagues and fool your boss making him/her believe you’re waiting for the end of a very long compiling process.

To use it, you just have to modify your code using :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Then you launch compilation for the duration you want, displaying meaningful messages in case your boss looks at your screen. Then, you have an excuse if your boss is not happy about your long pause, tell him/her: “Look, it’s compiling”.

Remember that this PataMorphism doesn’t pollute your code at runtime at all, it has only effects at compile-time and doesn’t inject any other code in the AST.

Usage

With default seed (5s compiling with msgs each 400ms)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

If you compile:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | |

With custom seed (1s compiling with msgs each 200ms)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

If you compile:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Macro implementation details

The code can be found on Github Maquereau.

Here are the interesting points of the macro implementation.

Modular macro building

We use the method described on scalamacros.org/writing bigger macros

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

input code evaluation in macro

The Seed passed to the macro doesn’t belong to the realm of Scala Macro but to your code. In the macro, we don’t get the Seed type but the expression Expr[Seed]. So in order to use the seed value in the macro, we must evaluate the expression passed to the macro:

1

| |

Please note that this code is a work-around because in Scala 2.10, you can’t evaluate any code as you want due to some compiler limitations when evaluating an already typechecked tree in a macro. This is explained in this Scala issue

input code re-compiling before returning from macro

We don’t return directly the input tree in the macro even if it would be valid with respect to patamorphism contract. But to test Macro a bit further, I decided to ”re-compile” the input code from within the macro. You can do that using following code:

1

| |

Using macro paradise

The maquereau project is based on Macro Paradise which is the experimental branch of Scala Macros.

This implementation of patamorphism doesn’t use any experimental feature from Macro Paradise but future samples will certainly.

Conclusion

This article shows that applying the concepts of pataphysics to Scala Macro is possible and can help creating really useful tools.

The sample is still a bit basic but it shows that a patamorphism can be implemented relatively simply.

I’ll create other samples and hope you’ll like them!

Have patafun!